Pelvic mesh is under fire. What should women with prolapsed organs do?

Marketing got ahead of the science of pelvic mesh, but experts see a role for the device in prolapse repair.

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-pmn.s3.amazonaws.com/public/RGTQIT64PRGUTGS4LLADUWUNRI.jpg)

As women get older, their pelvic organs tend to sag. That’s a normal part of aging.

But for millions of them, the sagging gets so bad — causing discomfort, urine leakage, or interfering with sex — that they resort to reconstructive surgery.

Synthetic plastic netting was supposed to be a big advance in surgery for what doctors call pelvic organ prolapse.

Instead, “pelvic mesh” has become one of the biggest mass torts in U.S. history. Medical device makers are paying nearly $8 billion to settle the claims of more than 100,000 women who suffered complications including pain, organ damage, infection, and incontinence.

Last month, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration took tough action, ordering the two remaining manufacturers of transvaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse to stop all sales.

Here’s the kicker: The FDA’s ban does not apply to all pelvic mesh products, and certain types remain an important option in selected cases, particularly for treating urinary incontinence. Experts say the benefits of using the devices depend on the surgical route, the therapeutic goal, the skill of the surgeon, and other factors that are still being studied.

“Mesh is not just a ‘bad news’ story,” said University of Pennsylvania urogynecologist Lily A. Arya, a specialist in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. “My ultimate message is one of hope, that ongoing research and clinical trials will help to determine the best treatment for a complex condition.”

How can women (and the men who care about them) sort all this out? Here are some things to consider.

Basic biology

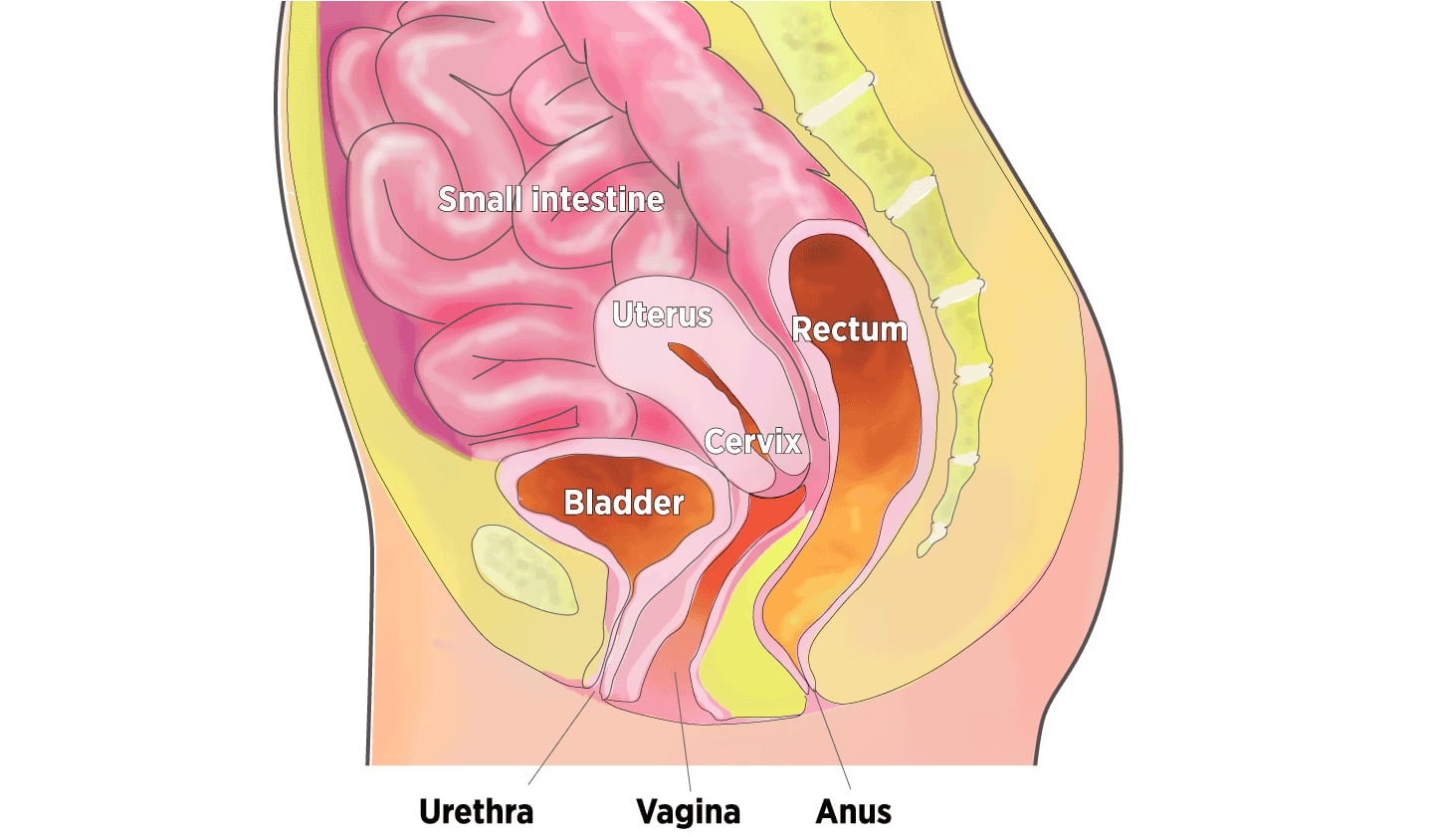

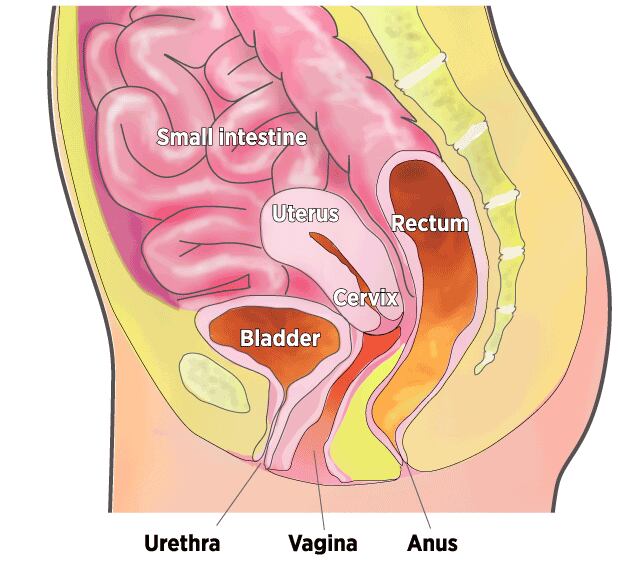

The pelvic floor, the muscular base of the abdomen, supports the vagina, uterus, bladder, bowel, and rectum. When these muscles are weakened by childbirth, chronic coughing, obesity, genetic factors, and inevitable aging, one or more pelvic organs may sink into or against the vagina. The top of the vagina also can drop down into that structure.

The good news is, prolapse is no more troublesome than wrinkles for most women.

“It is very, very common,” Arya said. “The mere presence of prolapse on a pelvic exam doesn’t mean it needs treatment.”

The bad news is, when sagging causes symptoms such as pelvic pressure, a vaginal bulge, lower-back pain, sexual dysfunction, or urine leakage, there are no easy, effective fixes. Conservative remedies include pelvic muscle exercises and a pessary, a removable silicone device that is inserted into the vagina much like a diaphragm or tampon.

Organs in the Pelvic Cavity

When muscles supporting the pelvic organs weaken, one or more of the organs can sag, or prolapse, into or against the vagina.

Many women turn to surgery. Over a lifetime, an estimated 7 percent to 19 percent of U.S. women have such a repair.

A variety of operations have been developed that use the woman’s own tissues to try to restore normal anatomy. But symptoms often recur and about a third of women need another operation, studies have found.

“For some women, the native tissue is too weak and you need to augment it,” said Cheryl Iglesia, an obstetrician-gynecologist and pelvic reconstructive surgeon at Georgetown University School of Medicine.

The debut of pelvic mesh

The evolution of mesh in prolapse surgeries was a classic example of marketing getting ahead of science.

Polypropylene mesh had been used since the 1950s to repair abdominal hernias. Gynecologists hoped mesh could reduce reoperation rates in prolapse surgeries, so in the 1970s, they began cutting it into desired shapes and inserting it through abdominal incisions. In the 1990s, they began cutting through the vagina, a minimally invasive route thought to shorten recovery.

“Over time, manufacturers responded to this clinical practice by developing mesh products specifically designed for pelvic organ prolapse repair,” says an FDA summary of the history.

None of the products, however, had to undergo clinical studies to see whether they actually were safe and effective. (And for gynecologists eager to do the delicate surgeries, manufacturers offered training courses that could be completed in just a few days.)

Pelvic mesh products came to market under a much-criticized medical device approval pathway called 510K. It allows diagnostic tests, surgical machines, heart valves, and other potentially risky devices to be “cleared” by submitting scientific evidence that they are equivalent to devices already on the market.

The first pelvic mesh, cleared in 1996, was a strip used as a sling to support the bladder and treat stress urinary incontinence — leakage that could be triggered simply by coughing or laughing. Bigger, bulkier products soon followed, most implanted “transvaginally” — through the vagina.

Between 2002 and 2013, the FDA says, it cleared more than 100 transvaginal meshes for prolapse — even as reports of serious complications mounted.

The FDA responded by taking an escalating series of actions beginning in 2008. It issued warnings that vaginal mesh products could contract, break, and “erode” into organs, causing infection, pain, vaginal scarring, urinary retention or incontinence, recurrent prolapse, and more. Then the agency reclassified vaginal mesh and ordered manufacturers to conduct clinical trials. Most makers withdrew their products, instead.

The two companies that conducted studies — Boston Scientific and Coloplast — “have not demonstrated a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness of these devices,” the FDA declared last month in ordering the end of sales.

Balancing risks and benefits

The FDA order does not apply to pelvic mesh placed through the abdomen, or to mesh used to treat incontinence.

The American Urogynecologic Society is among medical groups that say mesh slings are a vital option for incontinence, and the benefits are now established by studies.

The slings “are a standard of care for the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence and represent a great advance in the treatment of this condition for our patients,” the society says.

Arya, the Penn urogynecologist, thinks banishing all pelvic mesh “would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater.”

Shanin Specter disagrees. His Philadelphia law firm has won a string of verdicts for women treated with all types of pelvic mesh products. The most recent came a week after the FDA order. A Philadelphia jury awarded $120 million — believed to be a record in mesh cases — against Johnson & Johnson and its Ethicon subsidiary on behalf of an Altoona, Pa., woman who had mesh implanted to treat incontinence.

Also last month, Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson announced that Johnson & Johnson agreed to pay $9.9 million to avoid going to trial for failing to disclose risks in the instructions and marketing materials for surgical mesh devices, including those for incontinence. More than 60 gynecologists and surgeons sent a letter protesting the consumer-protection lawsuit, arguing that it might scare patients away from the best treatment.

Ella Ebaugh of Manchester, Pa., was unaware of the risks of mesh. She just wanted to stop leaking when she ran during softball games about 15 years ago. But several years after getting her second J&J mesh implant — the first didn’t help — she developed severe pain and urinating became difficult. Mesh had eroded through her bladder and urethra, causing irreparable damage. In 2017, she won a $57 million verdict, which is on appeal.

“When I grew up, you trusted your doctors. And I’m a trusting person. I think most women are,” Ebaugh, now 53, said in a recent interview. “J&J manipulated the data. They knew these risks and didn’t disclose them to doctors or patients. As a patient, you can do your research. But how do we know they’re telling the truth?”