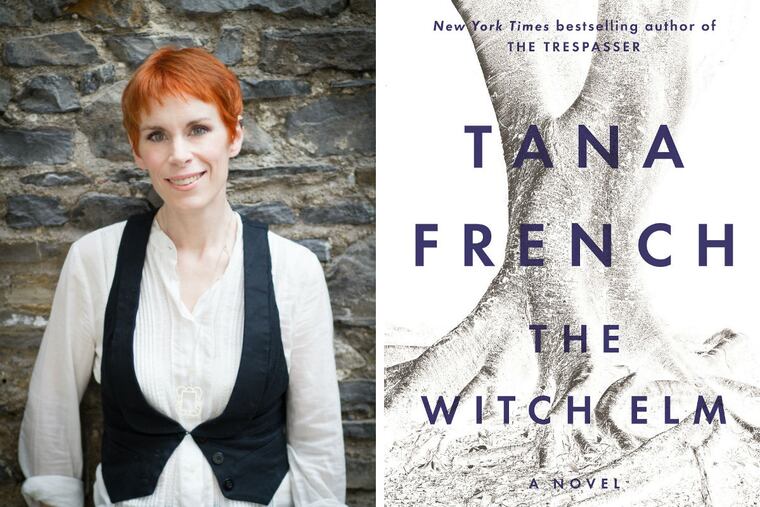

‘The Witch Elm’ by Tana French: Spooky but static for long stretches

The revered mystery novelist gives us a tale of a young, injured man who goes to his dying uncle's spooky mansion to keep an eye on him. There's plenty of mystery and an atmosphere of impending gloom – but much of the novel pretty much stands still.

The Witch Elm

By Tana French

Viking. 509 pp. $28

Reviewed by Maureen Corrigan

When it comes to literary suspense, can a reader ever have too much of a good thing?

That's the question that kept running through my mind while I was reading … and reading … The Witch Elm by Tana French.

French is rightly celebrated for her Dublin Murder Squad police procedural mysteries, such as Faithful Place and In the Woods. The present novel, a standalone psychological suspense tale, is a departure for her.

It's very eerie; it's also quite hefty and static for long stretches. Whether you find the novel satisfying will probably depend on how much you care about action versus atmosphere. French expertly crafts a cloud cover of thickening menace throughout this extended narrative, but the storm doesn't break until the very end. By then, even the most patient reader may be excused for being exhausted by all the bleak moodiness that preceded it.

In The Witch Elm, French reverses her usual allegiances: The police investigators here are the interlopers. In fact, they're regarded by our unreliable narrator as more foe than friend. That narrator's name is Toby, unreliable chiefly in that he has sustained a skull fracture and neurological damage after a brutal fight with two burglars who broke into his flat late one night. Before the break-in, Toby, who is in his 20s, says he was "basically, a lucky person." Blessed with good looks, athletic grace, supportive parents, and a doting girlfriend, he worked in public relations at a prestigious art gallery in Dublin. Now he is left with slurred speech and "patchy memory loss." What's worse, because Toby narrates his story retrospectively, we readers know the burglary is only the beginning of his long and nightmarish downfall.

After recuperating in the hospital for weeks, Toby is understandably uneasy about returning to his apartment. Determined to hold on to his independence, he resists the idea of moving in with his parents or girlfriend. A solution of sorts arrives in the form of a family misfortune: Toby's beloved bachelor Uncle Hugo has just been diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor. Hugo is a wonderful character — part Prospero, part Mr. Rogers. Toby is designated by his family to move in with Hugo and keep a companionable eye on him.

We readers know this sensible plan is doomed as soon as Toby describes the odd elusiveness of Ivy House, the ancestral Dublin mansion where Hugo lives. The taxi driver misses it, grousing that he never knew the gray-brick Georgian house was even there. The "double line of enormous oaks and chestnuts" that frame the mansion make it easy to miss and give "the inside its own micro-climate, dim and cool and packed with a rich unassailable silence."

Toby – along with his loyal sunbeam of a girlfriend, Melissa — move into Ivy House in the first quarter of the novel. For the remainder of the book, skeptical police detectives visit to question Toby about what he remembers about the burglary (as well as other things); Toby's cousins, aunts and uncles regularly drop in for chatty visits; Toby quietly helps Hugo with a genealogical research job; and Melissa leaves for work and returns home at night.

Throughout all these interactions, Toby second-guesses himself. Plagued as he is by memory loss, his paranoia mounts about strange references and significant glances the police or his family members exchange. There's very little movement (save for puttering around Ivy House and its sinister overgrown garden) and much internal speculation. In this respect, The Witch Elm is an extraordinary example of the suspense novel as less a work of drama than a work of suspended animation.

It would be nearly impossible for any novelist to conjure up a plot payoff that justifies all this anticipation. French tries, but the climactic revelations here inevitably seem too little too late.

Mystery and suspense fiction, along with police procedurals and crime fiction in general, often are disparaged as a second-rate literary form for their over-reliance on action-heavy plot. But I'd say that without any "bang, bang" for hundreds of pages, The Witch Elm becomes "boring, boring."

Maureen Corrigan is book critic for the NPR program Fresh Air and teaches literature at Georgetown University.